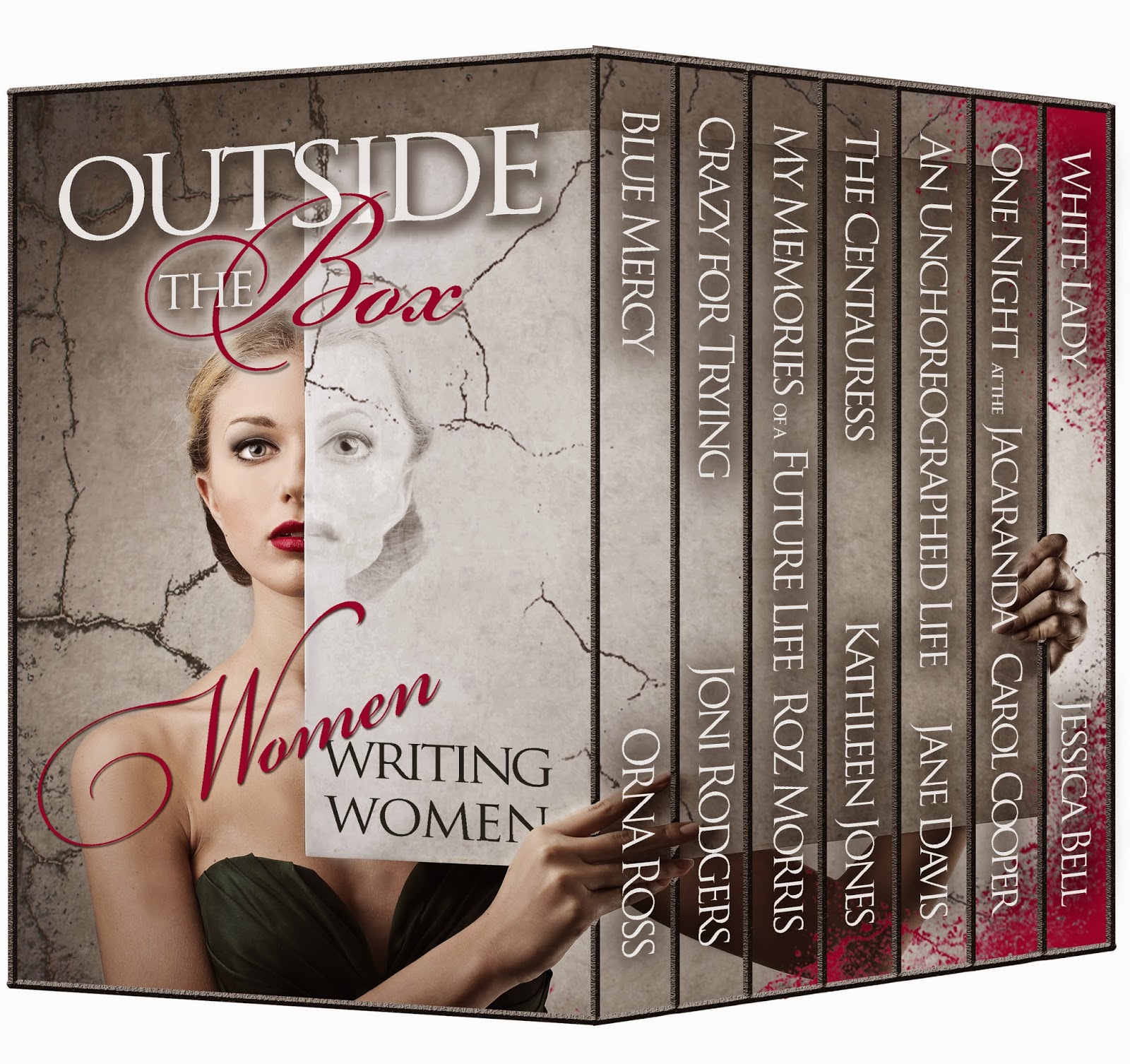

International Authors: Universal Themes

While mainstream publishing plays safe with predictable

stories and heroines who repeat the same familiar tropes, where are today’s

most ground-breaking authors? The answer is that they are self-publishing. Now,

seven of the most prominent female entrepreneurial authors have brought their

work together in a limited edition compilation of novels: Outside the Box: Women Writing Women.

The project is the brainchild of Jessica Bell, an Australian

writer living in Athens, Greece. A literary author and the Founder/Publishing Editor

of Vine Leaves Literary Journal, Jessica wanted to showcase the most exciting

fiction being released by authors who are in full charge of their own creative decisions.

“I couldn’t imagine collaborating with a finer group of writers,” Jessica said.

“The authors in this box set are at the very top of their game.”

The collection will be published in e-book format on February 20 (pre-orders from January 12) and available for just 90 days.

The box set introduces a diverse cast of characters: A woman accused of killing her tyrannical father who is determined

to reveal the truth. A bookish and freshly orphaned young woman seeks to escape

the shadow of her infamous mother—a radical lesbian poet—by fleeing her

hometown. A bereaved biographer who travels to war-ravaged Croatia to research

the life of a celebrity artist. A gifted musician who is forced by injury to

stop playing the piano and fears her life may be over. An undercover journalist

after a by-line, not a boyfriend, who unexpectedly has to choose between her

comfortable life and a bumpy road that could lead to happiness. A former

ballerina who turns to prostitution to support her daughter, and the wife of a

drug lord who attempts to relinquish her lust for sharp objects and blood to

raise a respectable son.

Jane Davis said, “This set of thought-provoking novels

showcases genre-busting fiction across the full spectrum from light (although

never frothy) to darker, more haunting reads that delve into deeper

psychological territory.”

But

regardless of setting, regardless of whether the women are mothers, daughters,

friends or lovers, the themes are universal: euthanasia, prostitution, gender

anomalies, regression therapy, obesity, drug abuse, revenge, betrayal, sex,

lust, suicide and murder. Their authors have not shied away from the big

issues. Some have asked big questions.

Orna Ross (founder-director of The Alliance of Independent

Authors, named by The Bookseller as one of the 100 most influential people in

publishing) selected Blue Mercy, a complex tale of betrayal, revenge, suspense, murder mystery - and surprise.

Joni Rodgers (NYT bestselling author) returned to her debut Crazy for Trying, a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection and a Discover Award finalist.

The stories behind some of the stories in Outside the Box

Carol Cooper

on One Night at the Jacaranda:

One Night at the Jacaranda is the first novel I’ve

created that got as far as the hands of readers. There’ve been other efforts: a

coming-of-age novel set in Cambridge, a children’s story about a stray dog, a

novel about a teenager coping with disability, and the chronicle of a female

surgeon in training. She never reached the top as she spent too much time

horizontal (like the manuscript, still languishing in a drawer somewhere).

Now I see that I was trying to fit into particular

places on bookshelves. By contrast, One Night at the Jacaranda, although it’s

contemporary women’s fiction, doesn’t nestle quite as neatly into a genre.

The idea came to me out of the blue. I was on a

flight to the USA, on my way to my father’s funeral. As I sat sipping a

much-needed gin and tonic, the idea for a story about a group of single

Londoners popped into my head. There’d be a struggling journalist, a lonely

lawyer, a newly single mother of four daring to date again.

I covered paper napkins with scrawled notes which

eventually developed into the novel. Finally I’d embarked on creating the kind

of book I’d want to read for pleasure. I wasn’t thinking about marketing

angles. I just wrote.

All the characters are made up. I don’t know where

ex-con Dan came from, and I’m glad I never had an au pair as manipulative as

Dorottya, but some of the influences are obvious. Although the stressed doctor

in my story is male, he takes on many of the frustrations I face in my day job.

Ditto the single mother, the freelance journalist, and the young man diagnosed

with cancer are all people I relate to.

I like to pretend that the story has nothing to do

with my father. For one thing, it would have been far too racy for him. He’d

have choked on a Harrogate toffee by page four.

Yet things fall into place when a parent dies, so

his influence is there. The deeper message of One Night at the Jacaranda is

that the characters can’t find happiness with someone else until they confront

who they themselves really are.

Over the years I’d authored and co-authored many

non-fiction books. The leap to writing fiction required new skills. But it was

refreshing to write what I wanted to write, without worrying about word counts

or thinking of appropriate illustrations. My experience in journalism shows, I

think, in my short scenes, cutting from one character to the next.

Medicine has a huge impact on my fiction. You can’t

put your patients in a book, but doctoring teaches you to observe. It’s no

surprise that many great writers have been doctors. While I can’t pretend to be

in the same league as Somerset Maugham, Michael Crichton, AJ Cronin, Khaled

Hosseini or Abraham Varghese, I’m grateful that my work brings me into contact

with such a wide range of people and situations.

Roz Morris on

My Memories of a Future Life

'I was always fascinated by tales of regression to

past lives,' says the author Roz Morris. ‘I thought, what if instead of going

to the past, someone went to a future life? Who would do that? Why? What would

they find?

‘Another longtime interest was the world of the

classical musician. Musical scores are exacting and dictatorial - you play a

note for perhaps a sixth of a second and not only that, there are instructions

for how to feel - expressivo, amoroso. It's as if you don't play a piece of

classical music; you channel the spirit of the composer.

‘I became fascinated by a character who routinely

opened her entire soul to the most emotional communications of classical

composers. And I thought, what if she couldn’t do it any more? And then, what

if I threw her together with someone who could trap the part of her that

responded so completely to music?’

Jane Davis on

An Unchoreographed Life

I was gripped by a 2008 court case, when, in an

interesting twist, it was ruled that a prostitute had been living off the

immoral earnings of one of her clients. Salacious headlines focused on the

prostitute’s replies when she was asked to justify her charge of £20,000 a

week. But the case also challenged perceptions of who was likely to be a

prostitute. The answer turned out to be that she might well be the ordinary

middle-aged woman with the husband and two teenage children who lives next door.

Whilst I was writing the novel, it became especially

relevant when change to the laws governing prostitution were proposed and

became headline news.

I grew up within the footprint of Nelson’s paradise

estate. The story of his mistress, Emma Hamilton, has always fascinated me.

Born into extreme poverty and forced to resort to prostitution, she later

became a muse for artists such as George Romney and Joshua Reynolds and a

fashionista by bucking the tight-laced trends of the day. Cast aside by an aristocratic

lover, she went on to marry his uncle. Completely self-educated, Emma

continually reinvented herself, mixing in diplomatic circles and becoming

confidante of both Marie Antoinette and the Queen of Naples.

But Emma’s story is unusual. I had a clear understanding

that, had I been born in another age, the chances were that, living in London,

I would have been either a domestic servant or a prostitute - but quite

possibly, both. Prior to 1823, domestics under the age of sixteen didn’t

receive a salary. They worked a sixteen-hour day in return for ‘bed and board’,

a very generous description of what was actually on offer. And, in return, when

they reached the age of sixteen, they were cast out onto the streets.

During my research, I used the Internet extensively

to source personal accounts, diaries, blogs and newspaper reports. How did

sex-workers come to the attention of the police and social services? What were

the main reasons they ended up in court? (The answer was generally tax evasion

and financial crime, things I knew about from my day job.) How did sex workers

see themselves? How did they view their clients? How did this perception change

if they stopped? I also consulted The English Collective of Prostitutes, who

very kindly allowed me to quote them in my fictional newspaper article.

And then I began to imagine what life was like for

the child of a prostitute. There was nowhere I could research that hidden

subject. And it is always the thing that eludes you that becomes the story.

Kathleen Jones

on The Centauress

The Centauress was inspired by a meeting with an

extraordinary Italian sculptor who was officially female, but was very open

about the fact that she was a hermaphrodite. She appeared to revel in her dual

sexuality, although there was an underlying note of tragedy in the stories she

told about her life. I began to wonder what it must be like to be born without

any specific gender identity and what it might mean for relationships. Almost by accident, I was present when she was being interviewed for her

biography and there were a lot of discussions about the ethical questions her

life story raised; how much the biographer should tell and how to protect the

people she’d shared her life with.

When she died, her story wouldn’t let me go. Meeting

her had changed my life – as she had changed many people’s lives, not always

for the better. Fictional episodes started writing themselves in my head, often

centred around one of her reminiscences.

I kept thinking ‘what if?’ and gradually the novel began to take shape.

Fiction can often be closer to the emotional truth of something than factual biography.

The Centauress is set in Istria – a very beautiful

part of Croatia that used to belong to Italy and has the turbulent historical

background I needed for the novel. The family of my main character, Zenobia,

has been torn apart by conflict. Living in Europe means living every day with

echoes of a violent, recent past; sharing your village or street with people

who may have betrayed your relatives, or be relatives of someone your family

also betrayed. Just below my house in Italy, at the bottom of the olive grove,

is a memorial to six young boys who were dragged from their houses and shot,

only a year before I was born.

As a

biographer myself, I’ve often felt uncomfortable ‘eavesdropping’ on the most

intimate moments of someone’s life, so

it’s not surprising that my narrator, Alex, became a biographer researching the

life story of celebrity artist Zenobia de Branganza, who is the Centauress of

the story. Alex has to struggle with the problems of her subject’s desire for

honesty and the wishes of friends and family not to have their lives exposed.

Alex has her own private tragedies, because the novel is also about surviving

some of the worst things that can happen to you. It’s this knowledge that

enables Zenobia to trust Alex with her most intimate revelations. And the message she gives to Alex is that it

is possible to heal and that you must always be ready to accept happiness and

love when it comes your way.

If you were

Queen of Publishing for a day, what’s one thing you’d change about the industry

as a whole?

Orna: The reason I love self-publishing so much is that it’s democratising and

it encourages diversity. Readers and writers together are now creating new

genres and books that London and Manhattan would never have published. If I

were Queen of Publishing for a day, I’d make it much more diverse. I’d love to

see a greater variety of voices at every level of the industry.

Jessica:

That’s a tough one. Can it stop being such a popularity contest and get back to

its roots? Focus on the writing, not how many followers the author has on

Twitter? In an ideal world...

Roz: I would ask for more literary awards to

open up to new writers. Not just to indies, but to all the new talent that

comes along. Too many literary awards are given on the basis of pre-existing

fame. If those authors genuinely wrote the best book of the year, then they

deserve the prize, but otherwise we should give awards to the genuinely

surprising, interesting and wonderful - not the usual suspects. Sometimes the

best book has been written by Hilary Mantel, Julian Barnes or Neil Gaiman - but

sometimes it’s been written by someone relatively unknown. And those are the

books that awards should be finding for us.

Carol: Although it should be obvious that there’s more than one way to

publish quality books, some people in both camps sadly take up entrenched

positions. Those in traditional publishing especially tend to snipe at the

other side, and the antagonism does nobody any favours. We shouldn’t be at war,

because in the end it’s all about the reader. I’d like to bring in a lot more

enlightenment and a bit more peace, but I may need more than a day to achieve

it.

Kathleen: I’d ban accountants

from the commissioning meeting! Books should be accepted on literary value

alone; it’s the only way to get a quality product. Readers quickly tire of

being sold ‘the next best thing’. They want variety, good stories, original,

surprising prose - they deserve the best, not some publicist’s idea of what

they can be conned into thinking is the best. Not only that, but many of the

books they buy purporting to be written by celebrities are in fact written by

someone else - usually a professional writer whose own work has been rejected

but who needs the money. To pass off a book in that way is fraudulent - at best

a con trick. We need to take the fake out of the fiction industry and writers

need to be free to write the books they want to write and readers want to read.

Jane: The options for those wishing to publish are now wider than ever

before, so I don’t think it’s the publishing industry I would change. It is the

perception of publishing and the value that we place on books and art that I’d

like to target. This year, I’ve been out speaking to librarians and booksellers

trying to encourage them to stock – and read – more indie titles. If Andrew

Lownie’s prediction is right, over 75% of books will be self-published by the

year 2020. Any outlet that refuses to stock indie titles will be doing readers

an enormous disservice by restricting choice. The other thing I’d like to be

able to do is to get out there and sell my books for the listed price. I hear

parents talk about spending £120 on trainers for their children - something that

will be outgrown in 6 months. People will fork out over £50 to see a band play,

they’ll happily pay £2.45 for a coffee or £3.60 for a pint of beer, and yet

they throw up their hands in horror at the idea of paying £8.99 for a

paperback. Is the real issue that readers’ needs are not being catered for?

£8.99 may seem a lot of money for something you don’t enjoy. I found the

results that Kobo have collated about books readers give up on half way through

very telling, with The Goldfinch and Twelve Years a Slave topping the list (the

books readers were told they should be reading), whilst the book they were most

likely to finish? Casey Kelleher's self-published thriller Rotten to the Core.

Joni:

Oh, Lord, I’d tell everyone to

take the day off and read a book. That’s the single most important thing

writers can do—for ourselves and for the book culture at large—but we leave

ourselves so little time for it.

%2Breduced.jpg)